In the previous article entitled “Climate Change and Emerging Markets: The Property Protection Gap Challenge”, we discussed the impact of climate change on natural catastrophes and property protection gaps. However, climate change also disrupts business, increases food insecurity and heightens health risks. All of these factors can impact on economic growth and development, leading to an increasing fiscal burden and even threatening social stability.

The broader impacts of climate change

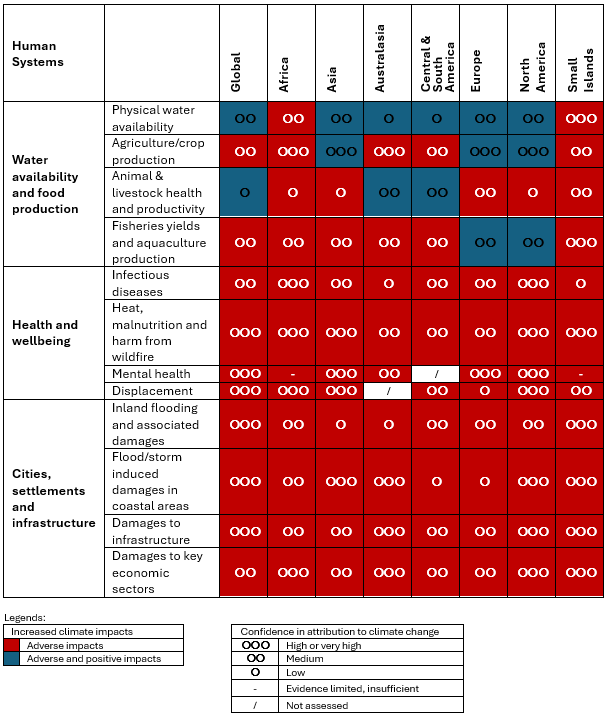

Beyond the physical impact of more frequent and severe extreme weather events, climate change has the potential to negatively affect economies and societies through various channels. This could manifest through reduced labour productivity or exacerbated limitations on water and food availability. For instance, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified four areas of substantial impact from climate change: (1) Water availability and food production, (2) Health and well-being, (3) Cities, settlements and infrastructure, and (4) Biodiversity and ecosystems (see Exhibit 1). In the following section, we will discuss each area except the last one, as the IPCC has not yet offered a global assessment of the impact direction.

Exhibit 1: Observed impacts and related losses and damages of climate change.

Source: IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 184 pp., doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

(1) Water availability and food production

Climate change is adversely affecting food and water security globally. Its impacts on agricultural productivity vary across high-, mid-, and low-latitude regions due to variations in temperature, precipitation patterns, and the ability of crops to adapt to changing conditions. Generally, agricultural productivity is negatively affected in mid- and low-latitude regions, while improvements may be observed in some high-latitude regions. In addition, ocean warming and acidification have adversely impacted food production from fisheries and shellfish aquaculture in certain oceanic regions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 98 million more people experienced food insecurity in 2020 compared to the 1981-2010 average.[1] Food insecurity is one of the reasons eroding human health globally.

Meanwhile, the IPCC acknowledges that around half of the world’s population currently experiences severe water scarcity for at least part of the year, due to both climatic and non-climatic factors. The intensification of climate change will exacerbate this trend, particularly in highly populated regions like South Asia, North China, Africa and the Middle East.[2]

(2) Health and well-being

Rising temperature, biodiversity loss and air pollutions, among other manifestation of climate changes, have both direct and indirect impacts on people’s health and well-being beyond food and water insecurity.[3] For instance, extreme heat can directly contribute to excess human mortality and morbidity. The combination of high temperatures and air pollutants can increase the burden of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, accelerating premature death. Natural calamities can also create mental health challenges arising from trauma and loss of livelihoods. Furthermore, the adverse impacts of climate change are unequally distributed, resulting in increasing income disparity and deteriorating social cohesions, which could lead to greater social fragmentation.

(3) Cities, settlements and infrastructure

Cities, especially mega-cities with populations exceeding ten million, are particularly at risks from climate change. The high concentration of people in relatively small areas renders residents more vulnerable to climate-related hazards such as heatwaves, floods and drought. Urban infrastructure can be severely damaged by extreme weather events or stressed by rising energy demand during prolonged hot periods. Business or service interruptions can further worsen the situation, particularly for economically and socially marginalised urban residents.

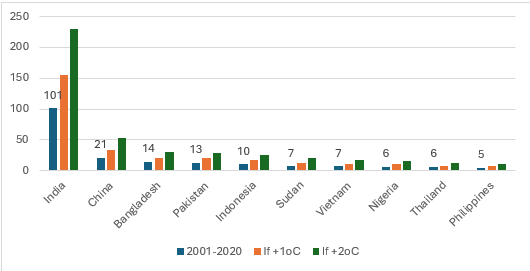

Global warming: A driver to lower productivity

According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2024 is on track to be the warmest year on record, with the global average temperature from January to September 2024 reaching 1.54°C above pre-industrial levels.[4] The rise in global average temperatures is leading to an increase in extreme heat event worldwide. In turn, heat exhaustion and heat stroke are escalating heat stress in the workplace, reducing labour productivity. This results in income loss for companies due to longer delivery time and reduced productivity. The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) estimated an economic loss of USD280 billion due to heat stress at work in 1995. This figure is expected to skyrocket to USD2.4 trillion by 2030, representing a loss of 80 million full time jobs.[5] An article published on Nature Communications in 2021 estimated that between 2001 and 2020, the global mean of labour lost from heat exposure for 163 countries with available data was 228 billion hours, or 81 hours per person (see Exhibit 2). The UNDRR estimates that labour productivity may decline by 50% if the temperature rises to 34°C.

Exhibit 2: Top ten countries with the heaviest labour losses from heat exposure in billions of hours per year.

Source: Parsons, L.A., Shindell, D., Tigchelaar, M. et al., Increased labor losses and decreased adaptation potential in a warmer world, Nature Communications 12, 7286, 2021

Note: The above graph shows the top ten countries with the heaviest labour losses in the 12-hour workday due to heat exposure weighted by the working-age population in outdoor heavy labour industries on 2001–2020 mean base. All units are in billions of hours/year.

In addition to extreme heat, global warming elevates sea levels and increases the frequency of extreme weather events, which could disrupt the efficient functioning of seaports and put global trade flows at risk. For example, it is estimated that 38% of global container throughput between 1980 and 2020 occurred in areas of high hurricane risk.[6] Flooding is becoming more frequent, causing 31% of economic losses from natural catastrophes between 1970 and 2019, and posing an increasing threat to both properties in flooded areas as well as the movement of cargo. Without effective adaptation measures, damage from riverine flooding is projected to increase by 1.7 times with 2°C warming by 2030 compared to 2010.[7] As maritime trade is expected to triple by 2050, supply chain disruption due to inland floods and coastal infrastructure malfunctions will undoubtedly increase.

Climate change stress healthcare and public finances

The stress on public finances can be viewed from various angles: loss from physical damage[8], increased health expenditure, financial loss due to business interruptions, and loss of tax revenue.

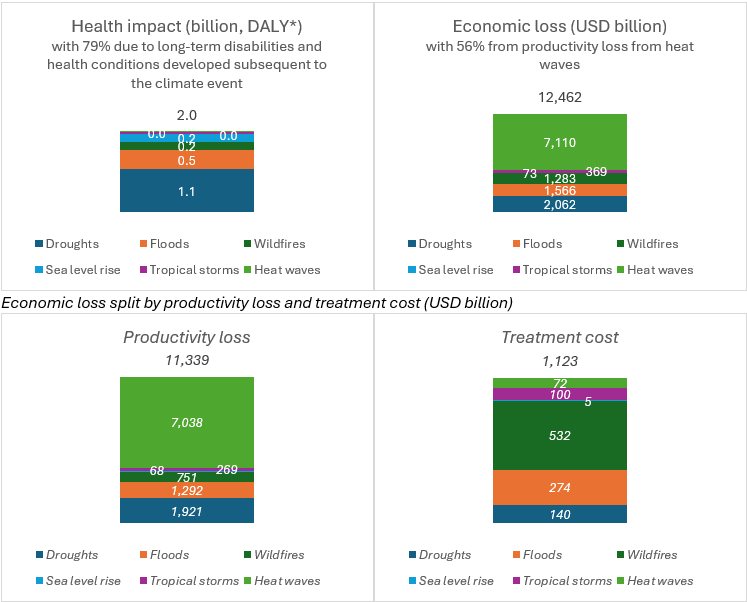

Global warming will increasingly strain national healthcare systems due to (but not limited to) excess morbidity from extreme temperature and the potentially rising risk of pandemics caused by habitat disruption and vector-borne diseases. An analysis by the World Economic Forum (WEF) and Oliver Wyman estimates that the health impact of climate change could reach 2.0 billion Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) by 2050 (see Exhibit 3).[9] This health impact includes premature deaths and individuals living with disabilities or conditions caused by weather events. The same report also projects that the economic impact from climate change could reach USD 12.5 trillion by 2050 (see Exhibit 3). This economic impact comprises of productivity losses due to health issues (e.g., absenteeism, reduced performance, or premature mortality) and the cost of treatment. This figure excludes the potential impacts from business and supply chain interruptions unrelated to health issue, such as damage to infrastructures due to climate change.

Exhibit 3: Projection of health and economic impacts by 2050 and by climate events.

Source: World Economic Forum in collaboration with Oliver Wyman, Quantifying the Impact of Climate Change on Human Health, 2024

* DALY stands for Disability-Adjusted Life Years, a time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLLs) and years of life lost due to time lived in states of less than full health, or years of healthy life lost due to disability (YLDs). One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.

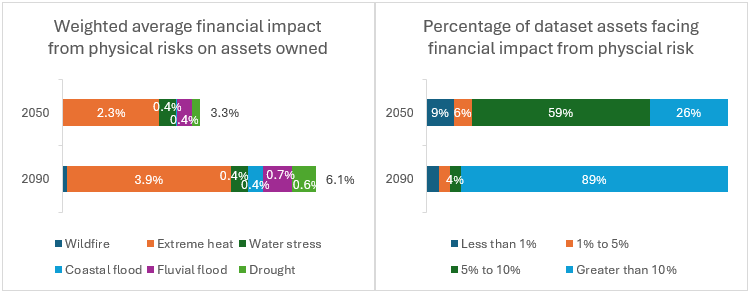

Beyond the immediate and direct short- to mid-term stress on public finances, long-term indirect stress would arise from the financial burden of climate change on companies. According to S&P Global Sustainable1 Physical Risk Exposure Scores and Financial Impact dataset, the cost of physical risks for companies in the S&P Global 1200 will be equal to an average of 3.3% (and up to 28%) per annum of their value of real assets held by 2050s without adaptation and resilience measures.[10] Extreme heat, water stress, fluvial flood and drought are currently the largest drivers of these losses (see Exhibit 4). Nonetheless, by 2090, coastal flooding is expected to become the predominant risk due to sea level rise, which by its nature takes more time to present significant financial impacts. The longer-term high financial impact associated with coastal flood is expected to be driven by the costs of repair and cleanup following such events. Overtime, this could filter through into lower government tax revenues.

Exhibit 4: Financial impact arising from natural hazards under the modest-high scenario in 2050 and 2090 for S&P Global 1200.

Source: S&P Global Ratings, Quantifying the financial costs of climate change physical risks for companies, 2023

Note 1: Financial impact is calculated at the asset level and represents the sum of financial costs arising from exposure to climate hazards for an asset, expressed as a percentage of the typical replacement value for a given asset type.

Note 2: SSP3-7.0 is a moderate- to high-emissions scenario, in which countries increasingly focus on domestic or regional issues, with slower economic development and lower population growth. This scenario projects a global temperature increase of 2.1°C by 2050.

Emerging markets are expected to bear the biggest burden

According to S&P Global Ratings, if global warming is not kept well below 2°C by 2050 and in the absence of effective adaptation plans, up to 4.4% of the world's GDP could be lost annually due to physical climate risks alone. Lower-income nations are expected to be 4.4 times more vulnerable than the developed ones, as they are disproportionately exposed to climate risks and less able to prevent permanent losses.[11]

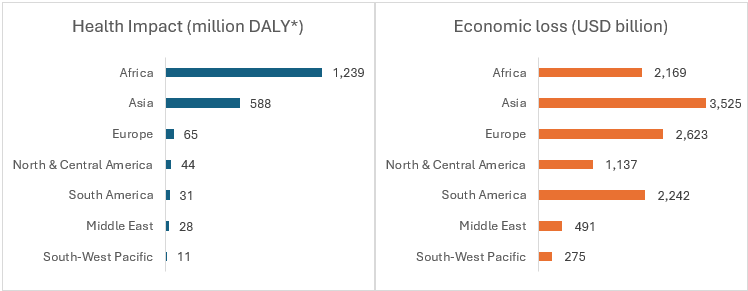

Additionally, an analysis by Oliver Wyman estimates Asia and Africa will experience the highest health impacts and economic losses (arising from health issues) by 2050 without any climate adaptation and mitigation measures (see Exhibit 5).[12] In Asia, this is partly due to the anticipated higher frequency of floods in densely populated coastal areas and the expectation that heatwaves will have the most adverse impact on productivity. In Africa, the economy will be negatively affected by productivity loss and increased healthcare costs.

Exhibit 5: Projection of health and economic impacts due to climate change by 2050.

Source: World Economic Forum in collaboration with Oliver Wyman, Quantifying the Impact of Climate Change on Human Health, 2024

* DALY stands for Disability-Adjusted Life Year, a time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLLs) and years of life lost due to time lived in states of less than full health, or years of healthy life lost due to disability (YLDs). One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.

The significant impacts of climate change on national economies, social stability, and fiscal balance underscore the urgent need for adaptation and mitigation measures. One important area to consider is strengthening the capacities of healthcare systems, particularly in emerging economies and densely populated areas. The preparedness of healthcare systems will significantly influence their ability to absorb potential health shocks from climate events before these shocks spill over into the broader ecosystem.[13] The extent of such spillovers can severely weaken the financial strength of sovereign states and hinder the economy’s ability to recover swiftly.

In conclusion, the potential impact of climate change on the global economy is substantial, though admittedly challenging to quantify. This underscores the uncertainty surrounding climate science, while also serving as an urgent call to action for governments and industries to integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies into their policies. Without such measures, economic losses and healthcare expenditures are expected to escalate dramatically. Additionally, social stability may be compromised, with rising income disparities, increased out-of-pocket expenses, and displacement of populations seeking better opportunities elsewhere. In a subsequent article, we will explore the role of the insurance and reinsurance industry in fostering climate resilience.

[1] World Health Organization, Climate Change, 2023

[2] Caretta, M.A., A. Mukherji, M. Arfanuzzaman, R.A. Betts, A. Gelfan, Y. Hirabayashi, T.K. Lissner, J. Liu, E. Lopez Gunn, R. Morgan, S. Mwanga, and S. Supratid, 2022: Water. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 551–712, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.006.

[3] The Geneva Association, CLIMATE CHANGE: What does the future hold for health and life insurance?, 2024

[4] World Meteorological Organisation, State of the Climate 2024 Update for COP29, 11 November 2024

[5] UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, GAR Special Report 2023: Mapping resilience for the Sustainable Development Goals, 2023

[6] UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, GAR Special Report 2023: Mapping resilience for the Sustainable Development Goals, 2023

[7] UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, GAR Special Report 2023: Mapping resilience for the Sustainable Development Goals, 2023

[8] This is discussed in Peak Re’s earlier article: Climate change and emerging markets: The property protection gap challenge, 2024. Therefore, we will not elaborate here.

[9] World Economic Forum and Oliver Wyman, Quantifying the impact of climate change on human health, 2024

[10] S&P Global Ratings, Quantifying the financial costs of climate change physical risks for companies, 2023

[11] S&P Global Ratings, Lost GDP: Potential impacts of physical climate risks, 2023. “Lower-income nations” refer to low and lower middle, based on World Bank data.

[12] World Economic Forum and Oliver Wyman, Quantifying the impact of climate change on human health, 2024

[13] The Geneva Association, CLIMATE CHANGE: What does the future hold for health and life insurance?, 2024

with Peak Re