Key messages:

- Tariffs, trade negotiations and policy-related economic volatility are here to stay, as US policies seek to bring about significant structural changes to reduce its trade and fiscal deficits. An escalating trade war could weaken global consumption, delay business investment decisions, disrupt supply chains and threaten overall global activity and trade.

- US household consumption, a key driver of global growth resilience, is at risk from the shifts in trade policies and budget cuts. Elsewhere, the EU and China have announced much-needed fiscal support to stabilise their domestic economies, which may partly offset the significant external headwinds.

- Emerging Asian economies are highly exposed to trade wars, not only to the direct impacts of tariffs and indirect impacts of a global trade slowdown but also to the interconnected supply chains with China. Economies dependent on foreign capital are vulnerable to financial market volatility and risk aversion.

Introduction

The exceptional changes in US geopolitics, trade and economic policy since early 2025 are reverberating across the globe. The global economic outlook has become more uncertain, as the current international world order and terms of international cooperation, which have been the norm since the 1980s, are recalibrated.

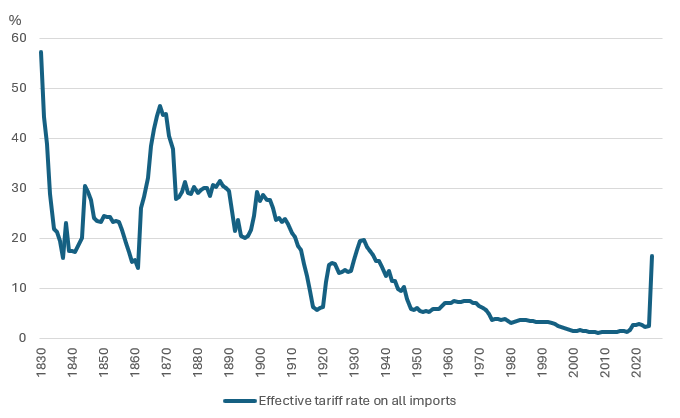

The US imposed a universal tariff of 10% on all trading partners, with additional “reciprocal tariffs” on about 60 countries, and sector-specific tariffs on the automobile, steel and aluminium sectors. While the “reciprocal tariffs” have been paused, the risk of reimposition looms, while several other sectors like semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, copper, and lumber are also under review for additional tariffs. If fully implemented, the sweeping tariffs will bring US import tariffs to the highest level since at least the 1930s (Figure 1). These shifts will also drive a rethink of global supply chains, accelerate deglobalisation, and reduce corporate profits and consumer purchasing power.

Figure 1: US effective tariff on imports jumped to a high not seen since the 1930s

Note: Effective rate as of 9-April-2025. Includes the “reciprocal tariff” calculations which have been paused, except for an increase in tariffs on China. Other sources using different "average" US tariff calculations could yield different results.

Source: Tax Foundation

Trade frictions put global growth at risk

The direction and extent of US tariffs remain difficult to predict. Nonetheless, the latest policy changes hint at a new era of American protectionism, with tariffs being used to address the US administration’s broader goals of reducing trade and fiscal deficits and increasing US employment, demanding significant structural shifts for the global economy.

US protectionism acts as both a demand-side and supply-side shock for the global economy, denting worldwide trade and activity. The two major contributors to resilient global growth over the last two years—the strength of the US consumer and emerging markets—are both likely to come under strain.

In its most direct impact, tariffs increase the prices of imported goods. A review of the 2018 tariffs by the US International Trade Commission showed that higher costs of the tariffs were mainly borne by American consumers or absorbed by American importers and manufacturers,[1] while having little impact on export prices in China. Higher retail prices lowered demand for the tariffed products, shrank trade volume and trimmed employment in the affected sectors.

Given that the increase in tariff rates is more aggressive now than in 2018-19, the dampening effect of higher import prices and inflation on the purchasing power of US consumers will be more significant. With household consumption accounting for 80% of US growth in 2024, and with the US having a roughly 30% share of global consumption, this has significant implications for the global growth. Estimates indicate that the real GDP growth impact of US universal and “reciprocal” tariffs could be about 1% for the US[2], about 2.5 for China[3] and 0.3%-0.5% for the Eurozone[4], in their first-order effects. Global GDP growth could slow to below 2% in 2025, from 3% in 2024, with global recession risks if trade wars escalate.

Evidence from the 2018-19 US-China trade war shows that bilateral tariffs had far-reaching negative impacts on third-country upstream suppliers within the manufacturing supply chain.[5] In addition, the heightened uncertainty creates supply-side shocks, paralysing supply chains and activity, and delaying business investment and hiring decisions. This, in turn, lowers consumer confidence and spending and, ultimately, activity across the globe.

Global growth is also likely to be persistently lower in the medium to long term. The WTO estimates that a continued decoupling between the US and China could drive a 2.4% contraction in global trade and a 7% long-term reduction in global real GDP growth compared to a no-decoupling scenario.[6]

Increased cost of goods and disrupted supply chains raise stagflation concerns

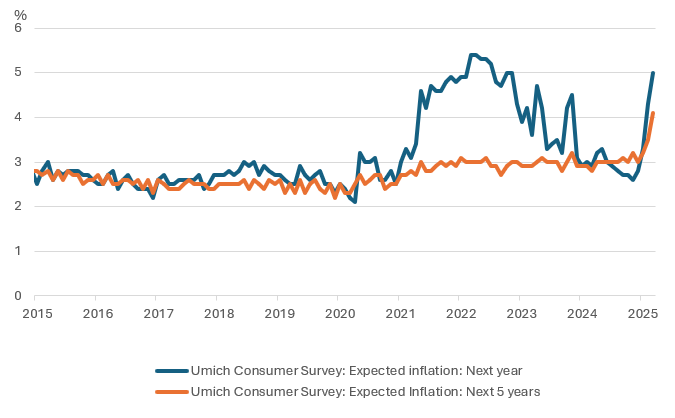

The direct impact of tariffs raises the retail price of imported goods to the US, with the announced “liberation day” tariffs expected to raise PCE (personal consumption expenditure) inflation in the US by 1.4 – 2.2 percentage points in their first-round impact.[7] Moreover, disruptions in supply chains, leading to supply shortages and delays also raise the cost of goods. This is already reflecting in consumer inflation expectations (Figure 2).

Evidence from past tariffs shows that shutting out cheaper foreign competition often leads domestic producers to raise prices too, due to a sudden increase in demand. For example, the 2018 tariffs on steel and aluminium caused domestic steel prices to rise by 5% and aluminium by 10%. Even as global demand fell subsequently, the gap between US and worldwide prices remained wider until these tariffs were later reduced.[8] The higher cost of raw materials substantially raised costs for downstream users. For instance, Ford and General Motors faced more than USD1 billion in higher costs or about USD700 per vehicle produced in North America.[9]

Figure 2: The US consumer inflation expectations have risen sharply

Source: CEIC

Global economies are increasing support for domestic growth

As external headwinds are on the rise, global economies have turned to fiscal policy to increase support for domestic growth.

In the EU, fiscal stimulus could fortify the sluggish growth recovery. A shift in the US’ geopolitical policy has pushed a rethink of EU fiscal policy, with a planned increase in defence spending to the tune of EUR 650 billion over four years.[10] More crucially, Germany, the largest economy, announced a significant fiscal stimulus of EUR 500 bn, or around 12% of Germany’s GDP, towards infrastructure development. While growth spillovers of defence spending tend to be lower, infrastructure spending is expected to bring much-needed growth support to help stir the German economy out of the technical recession of the past two years. While real wage growth has been positive in the EU, more policy support may be needed to boost consumption spending, especially amid heightened global uncertainties.

The impact of US import tariffs on China is considerable, though manageable, considering the US accounts for 15% of China's exports. At the same time, the Chinese Government has been accelerating policies since early 2025 to support domestic demand expansion. For example, the fiscal deficit is geared to reach a record-high of 4% of GDP in 2025, with support going to consumer durables, infrastructure, property sector and debt repayments. A 30-point plan to boost consumption through trade-in plans, subsidies, Hukou reform and a potential hike in the minimum wage has also been announced. There are signs that these measures are bearing fruit. China’s activity data, including retail sales and investment, recorded improvements in Jan-Feb 2025, while property sector indicators continue to point to a bottoming out. However, risks for the growth outlook, driven by the external growth slowdown, remain considerable and may need further government support.

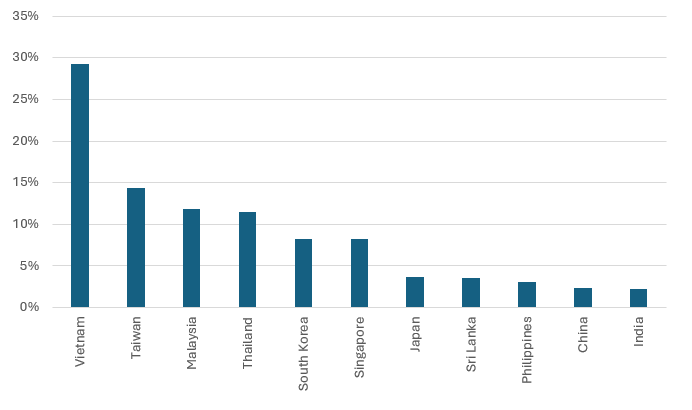

Asian Emerging markets’ high dependence on exports for GDP growth, as well as a high exposure to the US market, makes them vulnerable to changes in US trade policy. About 18% of the region’s exports are directed to the US, particularly in tech, autos and consumer goods. Regarding export exposure to the US, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and South Korea are the most vulnerable (see Figure 3). Traditionally, a 1% decline in US growth translates to a ~0.5% decline in growth for the trade-sensitive Asian economies. However, the impact of tariffs is further complicated by the interconnected nature of the regional supply chains. The big picture of US-China decoupling creates additional ripple effects throughout Asia's entire regional supply chain.

Figure 3: Asia exports to US as % of GDP

Source: CEIC

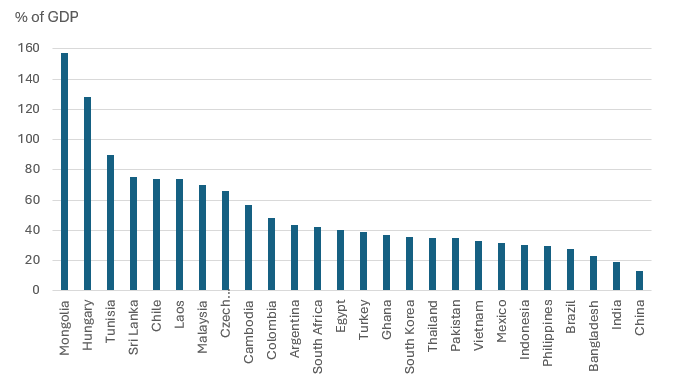

Emerging markets that rely on foreign capital are vulnerable to risk aversion. The prospect of slower global growth, higher inflation and heightened financial market volatility does not bode well for emerging markets. Periods of global risk aversion historically drive capital away from emerging markets, sending their economies into currency corrections and defaults on external debt. Economies with large external debts and current account deficits are particularly vulnerable. In this regard, Emerging Asia is relatively well-positioned with lower debts and more resilient financial markets. As a region, the Latin American economies have larger external debt burdens and wider current account deficits than Asia. Within emerging Asia, the economies of Mauritius, Mongolia and Sri Lanka have high external debt exposure.

Figure 4: External debt-to-GDP ratios for emerging market economies

Source: CEIC

An escalation in trade wars could worsen damage to the global economy, with spillovers beyond goods trade and tariffs

The discussion so far has not accounted for a significant escalation and retaliation from other trading partners in the emerging trade war. So far, some countries have offered conciliation against US tariffs, while others, notably China, have retaliated with counter-tariffs on US goods. However, given the US’ much smaller value of exports to China, retaliation has also taken other forms, such as export controls on critical rare earth materials and barriers for some US businesses from operating in China through its “unreliable entity” sanctions list and Export Controls list[11]. The European Commission has also warned of expanding the trade war to services, including taxing digital advertising revenues, as a potential trade war measure.

While not the base case, it may be worth considering how the trade wars may spill over beyond goods trade. Non-tariff barriers could be used to restrict operations for technology, engineering, financial, and consultancy services. A breakdown in international cooperation poses a significant challenge for digital and financial services, as these services rely on economic openness and common global standards.

Another consequence of an expanding trade war could be a fear of the US dollar’s reserve currency status being used in economic warfare. This may accelerate the diversification away from the USD as a reserve currency. Increased fragmentation among major economies may also give rise to alternative payment, trade and settlement systems, and diverging regulations across the globe.

Summary

The recent shift in US policies towards greater protectionism accelerates the trends of economic fragmentation and deglobalisation. However, the unexpected pace and intensity of US tariff implementation have shocked the global economy. Trade wars create lose-lose situations for all, including reducing disposable income for consumers, increasing business inefficiencies, and increasing uncertainty for all market players. For insurers, slower global growth hurts insurance demand, while tariffs raise claims costs. At the same time, rising global risks and diversification of supply chains could present opportunities for innovative risk solutions.

[1] United States International Trade Commission: Economic Impact of Section 232 and 301 Tariffs on US Industries, May 2023. Some estimates suggest the cost to an average US household, due to the 2025 tariffs, would be USD 4,600 per year. See Trump’s Tariff Pause Doesn’t Pause Economic Pain and Will Cost Families $4,600 Per Year - Center for American Progress.

[2] The Budget Lab: State of U.S. Tariffs: April 15, 2025

[3] Using China’s export trade elasticity of 0.6*, the estimated impact of 145% tariffs to contract China’s exports by 13%, and GDP growth by 2.6%. *World Bank Policy Research Paper: Trade Elasticities in Aggregate Models, Estimates for 191 countries, S Devarajan, June 2023

[4] Reuters: ECB's Lagarde spells out cost of trade war with US, 20 March 2025

[6] World Trade Organisation: Statement by the Director-General on escalating trade tensions, 9 April 2025

[7] Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: The Impact of Tariffs on Inflation, By Omar Barbiero and Hillary Stein, 6 February, 2025

[8] Reuters: What happened the last time Trump imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium, 11 March 2025

[9] Center for Automotive Research, US Consumer & Economic Impacts of US Automotive Trade Policies, February 2019

[10] Future of European defence - European Commission

[11] Holland & Knight: China's Comprehensive Retaliation Against US Tariffs, 8 April 2025

with Peak Re